The Little Rock Nine

On May 24, 1955, the Little Rock School

Board adopted a plan for gradual integration, known as the Blossom Plan, which

called for desegregation to begin in the fall of 1957 at Central High School. Under

the plan, students would be permitted to transfer from any school where their

race was in the minority, which would likely lead to Black schools remaining

segregated because few White students would chose to attend a Black school.

Federal courts upheld the Blossom Plan in response to a lawsuit by the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

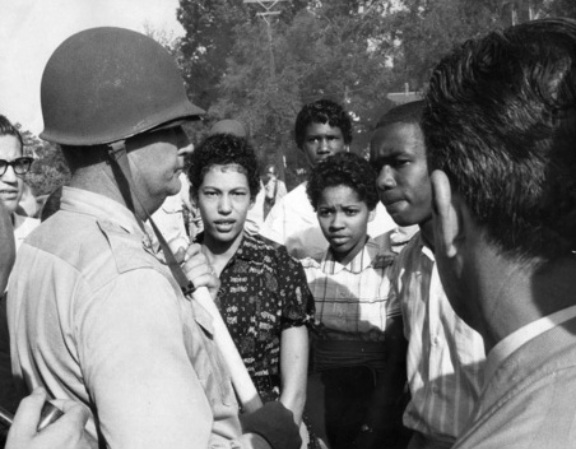

On September 4, 1957, the Little Rock Nine attempted to enter Central but were turned away by Arkansas National Guard troops called out by the governor. When Elizabeth Eckford arrived at the campus at the intersection of 14th and Park Streets, she was faced with an angry mob of segregationist protestors. She tried to enter at the front of the school but was directed back out to the street by the guardsmen. Walking alone, surrounded by the crowd, she eventually reached the south end of Park Street and sat down on a bench to wait for a city bus to take her to her mother’s workplace. Others of the Nine arrived the same day and gathered at the south, or 16th Street, corner where they and an integrated group of local ministers who were there to support them were also turned away by guardsmen.

The Nine remained at home for more than two weeks until the federal court ordered Gov. Faubus to stop interfering with the court’s order, Faubus removed the guardsmen from in front of the school. On September 23, the Nine entered the school for the first time. The crowd outside chanted, “Two, four, six, eight…We ain’t gonna integrate!” and chased and beat black reporters who were covering the events. The Little Rock police, fearful that they could not control the increasingly chaotic mob in front of the school, removed the Nine later that morning. They once again returned home and waited for further information on when they would be able to attend school.

The Nine remained at home for more than two weeks until the federal court ordered Gov. Faubus to stop interfering with the court’s order, Faubus removed the guardsmen from in front of the school. On September 23, the Nine entered the school for the first time. The crowd outside chanted, “Two, four, six, eight…We ain’t gonna integrate!” and chased and beat black reporters who were covering the events. The Little Rock police, fearful that they could not control the increasingly chaotic mob in front of the school, removed the Nine later that morning. They once again returned home and waited for further information on when they would be able to attend school.

Calling the mob’s actions “disgraceful,”

Eisenhower called out 1,200 members of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division—the “Screaming

Eagles” of Fort Campbell, Kentucky—and placed the Arkansas National Guard under

federal orders. On September 25, 1957, under federal troop escort, the Nine

were escorted back into Central for their first full day of classes.

After the Nine suffered repeated

harassment—such as kicking, shoving, and name calling—the military assigned

guards to escort them to classes. The guards, however, could not go everywhere

with the students, and harassment continued in places such as the restrooms and

locker rooms. After the 101st Airborne

soldiers returned to Ft. Campbell in November, leaving the National Guard

troops in charge, segregationist students intensified their efforts to compel

the Nine to leave Central. The Little Rock Nine did not have any classes

together. They were not allowed to participate in extracurricular activities at

Central. Nevertheless, they returned to school every day to persist in

obtaining an equal education.

Although all of the Nine endured verbal and physical harassment during their year at Central, Minnijean Brown was the only one to respond; she was first suspended and then expelled for retaliating against the daily torment by dropping her lunch tray with a bowl of chili on two white boys and, later, by referring to a white girl who hit her as “white trash.” Of her experience, she later said, “I just can’t take everything they throw at me without fighting back.” Brown moved to New York City and graduated from New Lincoln High School in 1959.

Although all of the Nine endured verbal and physical harassment during their year at Central, Minnijean Brown was the only one to respond; she was first suspended and then expelled for retaliating against the daily torment by dropping her lunch tray with a bowl of chili on two white boys and, later, by referring to a white girl who hit her as “white trash.” Of her experience, she later said, “I just can’t take everything they throw at me without fighting back.” Brown moved to New York City and graduated from New Lincoln High School in 1959.

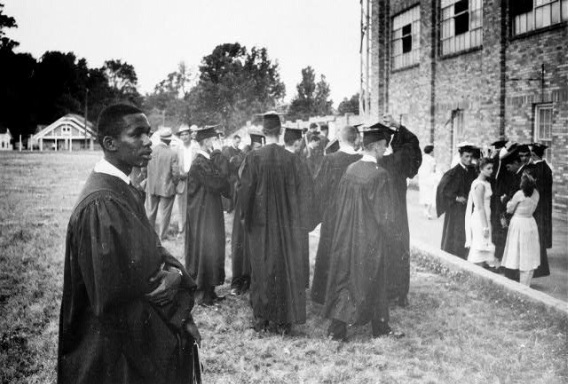

The other eight students remained at

Central until the end of the school year. On May 27, 1958, Ernest Green became

Central’s first black graduate. Green later told reporters, “It’s been an

interesting year. I’ve had a course in human relations first hand.” The other

eight, like their counterparts across the district, were forced to attend other

schools or take correspondence classes the next year when voters opted to close

all four of Little Rock’s high schools to prevent further desegregation

efforts.

The following video shows members of the Little Rock Nine, reflecting on his experiences during the crisis.

What does Terrence believe was the significance of the desegregation of Central High? What does the video suggest about the impact of this event?

What does Terrence believe was the significance of the desegregation of Central High? What does the video suggest about the impact of this event?

To learn more about the experiences of the Little Rock Nine and their opinions about what happened at Central High School, go here. This is a collection of interviews by the New York Times done in celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the desegregation of Central High School.